The surge in long-term liquified natural gas contracts from China is sustaining regional production and prolonging fossil fuel dependency

.jpg)

A Petronas floating liquefied natural gas (LNG) facility, near Bintulu in northern Borneo, Malaysia. China now has the largest collection of long-term LNG import contracts globally. Southeast Asian countries – especially Malaysia and Brunei – are among China’s key suppliers (Image: Rusdi Sembak / Alamy)

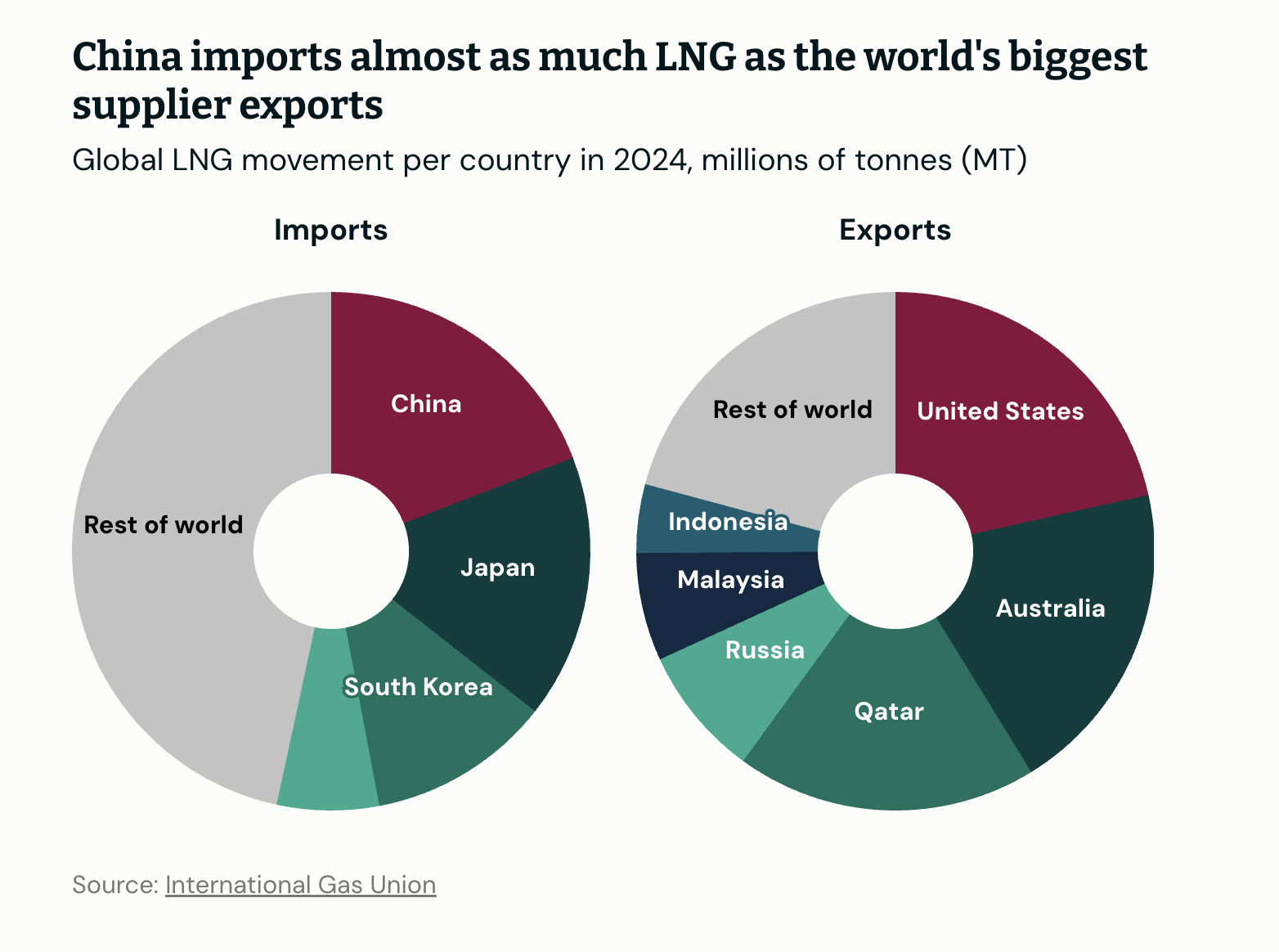

In 2021, the size of China’s liquefied natural gas imports surpassed every other country. After falling back to second place in 2022, it reclaimed the top spot in 2023 and stayed there in 2024. In addition, new data from BloombergNEF shows China also holds the most long-term contracts, with Southeast Asia – especially Malaysia and Brunei – among its key suppliers.

“In our 2030 outlook [published earlier this year], we expected China to be the major growth driver of liquefied natural gas demand, and following China is emerging Asia: Southeast Asia, and South Asia,” says Ziyue Daniela Li, a Beijing-based senior associate from BloombergNEF’s Asia Pacific Gas team.

Surging Chinese demand is prolonging liquefied natural gas (LNG) production, even as other markets (such as Japan and South Korea) reduce their use of the fuel. That provides a lifeline for major producers in Southeast Asia, such as Petronas, Woodside Energy, and Brunei LNG Sendirian Berhad. It may also be incentivising production or consumption increases in Southeast Asia, potentially locking in decades of emissions, and undermining regional and global climate goals. This worries climate change activists and scientists, who warn that continued LNG consumption will exacerbate global heating via both CO2 and methane emissions.

“Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines are all planning to have gas in their energy systems up to 2050,” says Amalen S, co-founder and Asia director of the activism non-profit Artivist Network, based in Malaysia. “Gas expansion is something to be concerned about, due to problems with gas leaks, pipes and, more importantly, the ecosystem and social destruction that comes about with expanded gas infrastructure along the coast.”

Geopolitics and energy security

China’s LNG imports rise came just as Asia’s two traditional major LNG-importing countries, Japan and South Korea, posted consumption peaks. Japan’s imports have been falling since 2015, owing to its shrinking population and growing renewable energy capacity. South Korea’s consumption peaked around 2020-2021 and is expected to decline further this decade. Chinese growth has more than offset those declines, driving the expansion of LNG production across Southeast Asia.

Malaysia, now fifth globally for LNG exports, has seen demand from China rise significantly in the past decade to become its second-largest market. Brunei’s exports to China have also risen and it signed a five-year LNG contract with state-owned PetroChina in May.

According to BloombergNEF’s Li, China is expected to maintain and even increase these import figures, at least until 2035. It will have the world’s largest collection of long-term LNG contracts and continue growing its orders from all the major LNG exporters.

What China will do with all this LNG remains a key question. Furthermore, there are concerns that contracted LNG imports could outpace domestic demand, which could slow down China’s transition to renewable energy sources. “China might end up with an oversupply of LNG,” says Erica Downs, a senior research scholar focusing on Chinese energy markets and geopolitics, at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy.

“LNG faces competition from coal and renewables, both of which are perceived as providing greater security of supply because they are domestic energy resources and cheaper sources of power.”

One solution is to trade it. Over the past decade, China has vastly expanded its natural gas infrastructure. This has meant new terminals, vessels and infrastructure to transport LNG from ports to factories and gas-fired power plants – and, potentially, abroad. “The existing import capacity and that which is currently under construction will together exceed 200 million metric tonnes a year, but our demand is 60 million metric tonnes and may rise to 100 million by the end of the decade,” says Li. “We have more than enough.”

A cargo ship loaded with Malaysian LNG docks at Yantai port in eastern China’s Shandong province. New LNG infrastructure – terminals, vessels, transport links – has been vastly expanded in China, and the country imported the most LNG globally in 2021, 2023 and 2024 (Image: Cynthia Lee / Alamy)

A new report from Solutions for Our Climate, a South Korea-based non-profit, says China has the most LNG vessels under construction, with 61 on order. Alongside the 112 already in service, this will give China the second-largest fleet in Asia after Japan.

“A lot are built for importers, and it is a sign that Chinese buyers want to play a bigger role in global trade,” says Li. “You need to have ships to have more flexibility.”

Here, Japan provides a model: for years it has imported far more LNG than it consumes domestically, re-exporting it to Europe and Southeast Asia. China could do the same, but most LNG contracts restrict resale. Among the exceptions is the world’s top LNG exporter, the US, which is a growing source of LNG despite ongoing trade tensions.

“China has a lot more US contracts coming on board up to 2030,” says Li. “Now, it’s six million metric tonnes, and will increase to 26 million.”

“If China does end up with an oversupply of natural gas, I expect China’s LNG buyers to sell the cargoes elsewhere,” says Downs. “Some companies have been building up their LNG trading desks in recent years as they look to increase their role as global LNG traders, and their profits from LNG trading.”

Li sees Southeast and South Asia as likely destinations for excess Chinese LNG, noting Thailand, the Philippines and India as potential growth markets.

Climate and energy transition

China’s expanding LNG consumption appears to contradict its stated aims of peaking fossil fuel emissions and shifting to renewable energy sources. But rising energy security concerns, stoked by conflicts in the Middle East and Eastern Europe, have impacted global energy trade and reshaped its priorities.

Countries in Southeast Asia are being sold the idea that gas is a transition fuel,

and being pushed and locked into gas

- Amalen S, Asia director, Artivist Network

“While China is expecting to peak emissions and fossil fuel consumption, either imminently or within the next few years, at the same time, there is a big effort to strengthen energy security,” says Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air. “Peaking fossil fuel emissions doesn’t mean that your reliance goes away. It just means that it declines over time.”

For countries like Malaysia and Brunei, Chinese LNG growth has enabled continued exploration of oil and gas fields, and investments into new fields. For example, the Kasawari gas field off the coast of Borneo, estimated to contain 3.2 trillion cubic feet of natural gas resources, started production last year.

Other countries in the region are also expanding their use of LNG. Thailand began importing LNG in 2020 and has rapidly expanded its infrastructure in the past few years. It has already become Southeast Asia’s top importer. Much of Thailand’s LNG comes from the spot market, meaning resales from China could play a larger role there in the future. The Philippines started importing LNG in 2023 through two LNG-receiving terminals, and is also seen as a potential growth market. Cambodia is exploring building an LNG terminal to import natural gas for power generation.

“Countries in Southeast Asia are being sold the idea that gas is a transition fuel, and being pushed and locked into gas,” says Amalen. “But gas could lead to inflation and financial risk.”

Amalen is also concerned that expanding the use of natural gas in Southeast Asia via more LNG infrastructure is harmful to the growth of renewable energy.

“We need to be pushing for renewables as soon as we can, mainly for energy independence,” says Amalen. “Ignoring this for gas, as a ‘transition fuel’, will harm energy access and accessibility and lock us into gas dependence for 20 years – or more.”

This article was originally published on Dialogue Earth under the Creative Commons BY NC ND licence. Read the original article.

.jpg)