Indonesia has been publicly rebuked at COP30 with a “Fossil of the Day” award after civil society groups accused its delegation of echoing fossil fuel and carbon industry lobbyists during negotiations on Article 6.4, the U.N.’s new carbon market mechanism.

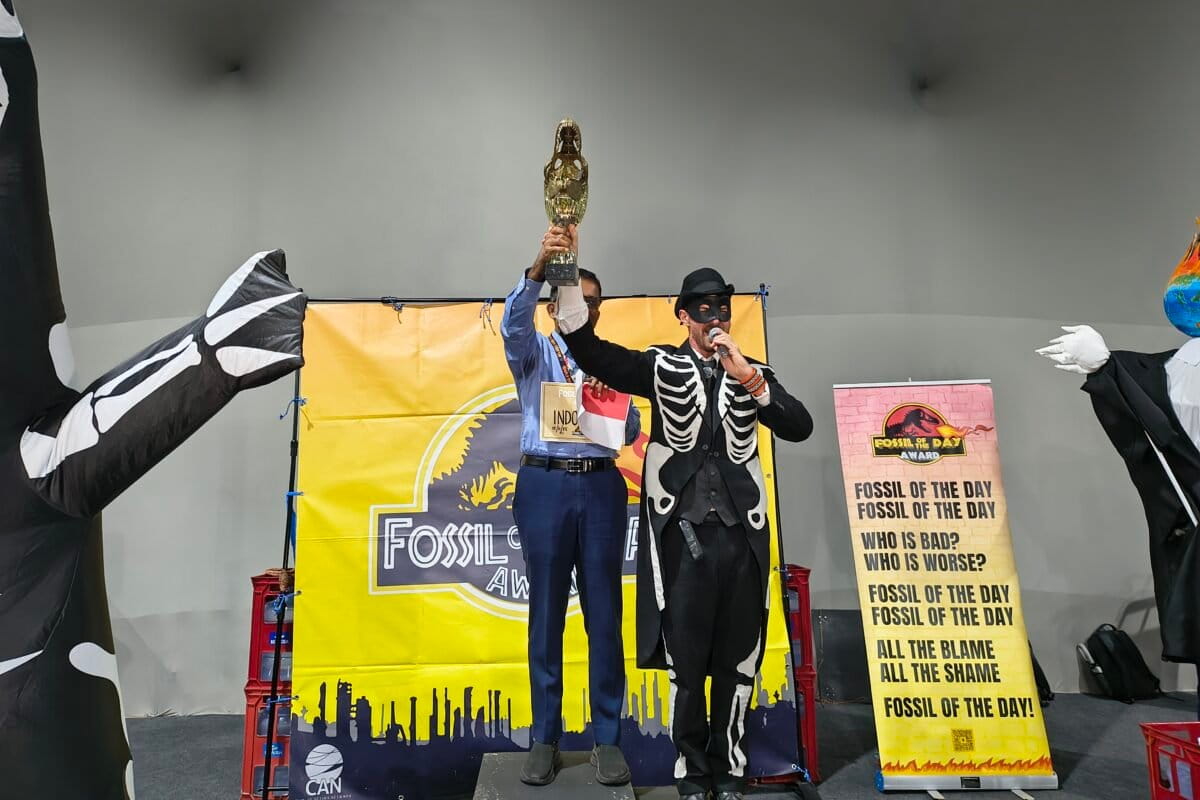

Indonesia received the “Fossil of the Day” award at COP30 after civil society groups accused its delegation of echoing fossil fuel and carbon industry lobbyists during negotiations on Article 6.4, the U.N.’s new carbon market mechanism. Image courtesy of CAN International.

For the Indonesian delegation at COP30, the summit was meant to be a showcase for its climate diplomacy and growing carbon market ambitions.

Instead, it was publicly called out for the first time in the history of the U.N. climate talks, receiving the “Fossil of the Day” award on Nov. 15 for allegedly allowing fossil fuel lobbyists to shape its official negotiating stance.

The award, handed out daily by the Climate Action Network (CAN) International, a coalition of more than 1,900 civil society groups, accused Indonesia of echoing talking points from industry groups during negotiations on Article 6.4 of the Paris Agreement, the U.N.’s new carbon market mechanism.

Observers said this raises questions about Indonesia’s credibility, its role among developing countries, and the integrity of the carbon credits it hopes to sell internationally.

Indonesia’s delegates to COP30 include at least 46 individuals from fossil fuel companies, according to a database compiled by the Kick Big Polluters Out coalition. This makes Indonesia among the developing countries with the largest number of fossil industry delegates.

These include officials from the state-owned oil and gas company, coal and mining conglomerates, fertilizer producers dependent on gas, and heavy-industry firms — a cross-section of industry that critics say resembles a coordinated national fossil fuel bloc rather than a handful of incidental observers.

Greenpeace Indonesia country director Leonard Simanjuntak said this reflects long-standing political realities.

“The presence of 46 fossil fuel industry lobbyists as part of Indonesia’s delegation lays bare the government’s alignment with the fossil-fuel oligarchy,” he said.

Echoing lobbyist talking points

What set Indonesia apart this year, CAN said, was not just who joined the delegation but how closely Indonesia’s intervention in the Article 6.4 negotiations mirrored a recent open letter co-signed by groups with an interest in carbon trading. (CAN noted that these include environmental NGOs like Conservation International, which it said “develops and sells carbon credits from conservation groups and industry players.”)

The letter argued that Article 6.4’s newly adopted safeguards were too strict and risked excluding nature-based carbon projects — industry parlance for protecting forests or planting trees, and then selling credits for the carbon that these ecosystems are supposed to keep out of the atmosphere.

Advocates of stronger integrity standards say the letter’s criticism is misleading. Isa Mulder, a policy expert on global carbon markets at Carbon Market Watch, was inside the negotiation room when the Indonesian delegation made its case, appearing to quote verbatim from the letter.

“What Indonesia was doing was to reiterate and sometimes even just use the phrases that are in that letter, the demand from that group,” she told Mongabay. “That’s really surprising for us. Not only [did] they say something related to Article 6.4, but also the exact talking points.”

Mulder, who has followed Article 6 negotiations for years, said she’s never seen a national delegation so explicitly echo industry-aligned messaging. That Indonesia — a country that has rarely taken the floor on Article 6.4 discussions — did so this time made it even more unexpected, she said.

“[It would] be different if it comes from other countries that have held this position [for a long time],” she added.

CAN called Indonesia’s intervention “the most blatant example yet of corporate capture by a developing country at COP30.”

It also criticized Indonesia for using its pavilion at the conference to aggressively market carbon credits to offset ongoing fossil fuel emissions — at a summit meant to phase those emissions out.

PLN’s Evy Haryadi and GGGI’s Sang-Hyup Kim sign an MoI on Indonesia–Norway renewable energy carbon trading during the Seller Meet Buyer session at the Indonesia Pavilion, COP30 Belém, witnessed by Ministers Hanif Faisol Nurofiq and Andreas Bjelland Eriksen. Imaga courtesy of the Ministry of Environment.

Government response

Indonesia’s environment minister, Hanif Faisol Nurofiq, rejected the accusation that fossil fuel lobbyists are shaping the country’s negotiating stance. He said observers had misunderstood Indonesia’s intervention because it was taken out of context.

“There’s a misunderstanding in the narrative — it actually wasn’t like that,” he said. “The statement that was taken came from that context, but only a fragment was used, without the full explanation. So our negotiators will clarify it.”

Hanif did not directly address the claim that Indonesia had repeated industry talking points, focusing instead on the idea that the intervention had been clipped or misinterpreted.

What Article 6.4 requires

Article 6.4 is designed as a centralized U.N.-supervised carbon-market mechanism with safeguards intended to prevent the types of low-integrity offsets that have long plagued voluntary markets.

Countries agreed last year on a set of standards, including rules on permanence — ensuring that carbon stored or removed through a project will not be reversed, so that credits used to offset fossil emissions do not undermine the Paris Agreement.

A coalition of groups promoting nature-based climate solutions, including Conservation International and The Nature Conservancy, has urged the UN to revisit those rules. CI argues that the current approach risks excluding forest projects.

“If the guidance on carbon markets under Article 6.4 doesn’t course correct adopted standards and provide guardrails for future work next year, nature-based solutions might be excluded in practice,” Florence Laloë, CI’s global senior director of climate policy, said at COP30.

Mulder called this line of argument “disingenuous.”

“It’s not about excluding activities, but guaranteeing permanence, making sure whatever [is] achieved under 6.4 can actually make up for whatever it’s used to offset,” she said.

CAN said many of the groups that co-signed the letter have direct or indirect financial stakes in selling carbon credits — “precisely the players who stand to gain from diluted rules.” Among them is the International Emissions Trading Association (IETA), whose delegation includes 58 fossil fuel lobbyists and whose board features major oil and gas companies.

Some of the co-signees of the open letter, like the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and Rainforest Alliance, are also CAN members. But CAN said it has positions that reflect the majority, not all its members.

Why Indonesia wants Article 6.4 changed

A member of the Indonesian delegation told Mongabay the government believes Article 6.4’s requirements should be more aligned with Article 6.2, a separate provision that allows countries to trade carbon credits through bilateral deals with far looser and less transparent oversight.

Under Article 6.2, most details of these deals remain confidential, said Juliette de Grandpré, a senior expert at the NewClimate Institute, a German think tank.

“As a result, whether these agreements really lead to higher ambition or not is left to the countries’ interpretation,” she said.

Article 6.4, by contrast, calls for a centralized supervisory body, public oversight, and strict rules on methodologies and monitoring.

“I think Article 6.4 is much more robust than 6.2,” de Grandpré said. “The system is finally operational. I don’t see the point in reopening everything now.”

She said attempts by some countries to weaken the rules surfaced at COP30 once they realized that complying with strict safeguards would require substantial effort. That’s why the Indonesian delegation’s position is alarming, de Grandpré said.

“There’s a risk that other countries might join them, which could put pressure on the integrity of the system,” she said.

Participant in the Indonesian Pavilion in the Blue Zone, on the ninth day of the 30th Conference of the Parties (COP30). Photo byAntonio Scorzas/COP30

Inside the delegation: ‘Party overflow’ badges

All 46 fossil fuel industry representatives linked to Indonesia were accredited as “party overflow” delegates — individuals allowed to enter the main COP venue when a country’s official quota is filled.

These individuals aren’t negotiators but may include industry representatives with close government ties.

Although a delegate with an overflow badge isn’t automatically permitted access to all negotiation rooms, enforcement varies across meetings, according to a 2025 report by Transparency International. The inconsistency of the rules means industry representatives can enter negotiation spaces and influence discussions, observers warn.

The surge in fossil fuel lobbyists at COP30 has intensified these concerns.

Kick Big Polluters Out recorded 1,600 fossil fuel lobbyists at the summit — one in every 25 attendees — the highest proportion of any COP.

For youth activists, the implications are severe.

“Every space given to the fossil fuel industry at COP is a space taken away from our future,” said Ginanjar Ariyasuta, coordinator of Climate Rangers, an Indonesian activist group. “How can young people hope for a fair, sustainable and prosperous future if the very actors of the crisis are given the stage to steer the discussions?”

For Indonesia, its climate reputation is at stake.

“In a year where polluter presence is higher than ever, and where corporate capture threatens every outcome on the table,” CAN said, “Indonesia stands out for handing the microphone directly to the very interests driving the crisis while its own people are experiencing severe climate impacts.”

Author: Hans Nicholas Jong

This article was originally published on Mongabay under the Creative Commons BY NC ND licence. Read the original article.

.jpg)