Coal mine on a barge in Indonesia. Image by Rhett A. Butler/Mongabay.

Indonesia’s state-owned power utility has backed away from promises to rapidly expand its use of renewable energy, opting to focus instead on building more power stations that burn fossil fuels.

The country’s electricity monopoly, PLN, will expand by more than one-fifth how much electricity it generates from gas and coal by the middle of the next decade, according to the company’s Ten-Year Supply Development Plan (RUPTL).

While PLN also intends to triple how much electricity it gets from renewable sources, most of the expansion in green energy will need to wait until the early 2030s as the utility struggles to first meet soaring demand for electricity. Indonesia’s grid is, for now, unable to accommodate on-again-off-again renewable energy, the company has said.

The question for PLN is “how can renewables, which are indeed variable, and fossil fuel-based power plants be sewn together?” Darmawan Prasodjo, PLN’s president director, told a parliamentary commission last month ahead of the release of the supply blueprint.

PLN unveiled a slide presentation of its RUPTL late last month, foreshadowing a massive buildout of solar and other renewable energy over the next 10 years. The biggest initial focus, though, will be new gas- and coal-fired power plants between now and 2029. Renewables will comprise a slightly smaller share of the planned expansion until the end of this decade.

But on June 3, the utility published the full version of its 1,200-plus-page electricity supply blueprint which underscored doubts for some analysts that PLN would countenance the country’s shift to renewables anytime soon.

One example: strict caps on rooftop solar.

PLN will let households and businesses generate no more than 3 gigawatts of electricity — enough to supply a little less than 3,000 Indonesian households on average.

By comparison, in Vietnam, where the government last year introduced rules letting rooftop solar panels owners sell their excess energy to the grid, installed capacity of rooftop solar panels is already nearly 10 GW.

PLN’s cap on rooftop solar, roughly double the previous cap, is hard to square with PLN’s planned 565.3 trillion rupiah ($34.8 billion) investment in new substations and some 48,000 kilometers (29,800 miles) of additional transmission lines, analysts said. That’s because the investment aims to help the country’s grid accommodate fickle and often far-flung renewable sources.

The RUPTL also makes no mention of early retirement of coal-fired power plants like the 660-megawatts Cirebon-1 that had been slated to shut down in 2035 — seven years earlier than planned — under a pilot program funded by the Just Energy Transition Partnership.

“The RUPTL is a clear move to prioritize a fossil fuel rollout — mostly gas — in the next five years,” Katherine Hasan, a Jakarta-based analyst with the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, told Mongabay.

.jpg)

Solar panels in Bali, Indonesia. Image by Selamat Made via Flickr (CC BY 2.0).

Poor track record

In total, PLN says it will need to add an extra 69.5 GW of new power generating capacity over the next 10 years, more than 60% of which will come from renewable sources.

Between now and the end of this decade, it will add nearly 13 GW of generating capacity fueled by gas and coal. A little more than 12 GW of renewable energy, including solar, hydro, wind and geothermal, will come online by 2029, according to the plan.

Fossil fuels, including coal, gas and even diesel, accounted for more than 88% total power generation capacity of 74.6 GW as of 2024, according to the RUPTL.

But hardening attitudes among foreign lenders against fossil fuels will make it tough for PLN to find the backing for new gas- and coal-powered generators, Mutya Yustika, an energy finance specialist at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), told Mongabay.

PLN instead would need to borrow closer to home, Yustika said.

“The most accessible option for funding for [fossil fuels] remains Indonesia’s state-owned banks, yet their financial capacity is limited, restricting the scale of fossil fuel investments,” Yustika said.

The relative readiness of foreign investors to take a punt on renewables projects, despite the regulatory headaches of getting projects off the ground here, may prod PLN to bring them forward.

Still, PLN has a bad habit of overpromising and underdelivering when it comes to clean energy, which may have turned off more risk-averse investors.

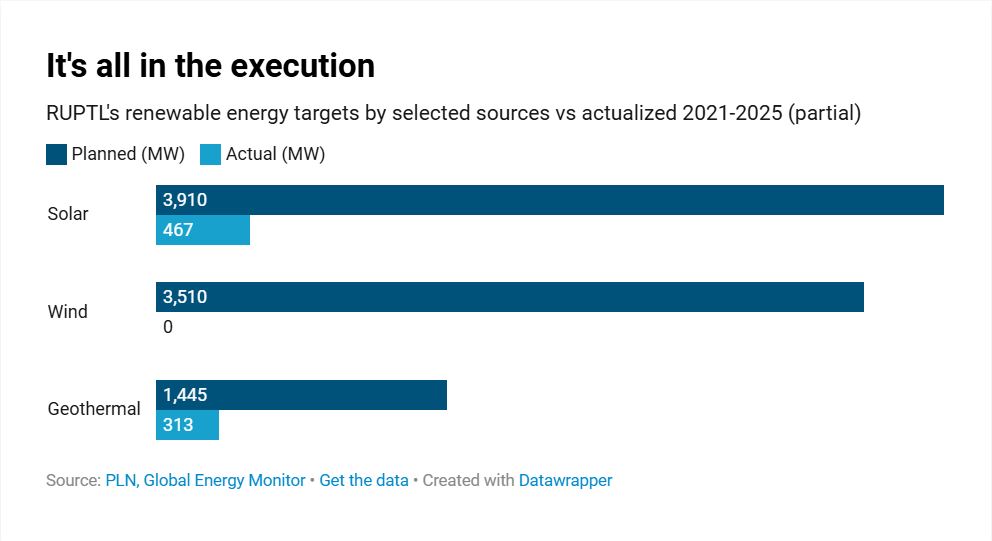

Under the previous RUPTL, PLN committed to developing 21 GW of renewable energy generating capacity, implying 2.1 GW worth of solar panel arrays and wind farms each year. The real rate was 0.6 GW per year.

PLN promised 3.9 GW of solar projects during the first five years of this decade, but it barely delivered a tenth of that amount.

To build anything close to 43 GW of extra generating capacity from renewables, PLN will need to lift some of the rules that govern the segment.

In August, Indonesia lowered its minimum domestic content requirements to 20% from 40% for solar power plants, but the move came with strings attached. Projects needed to get approval from the minister of energy and mineral resources and have signed a supply agreement with PLN by last December.

“The weak realization of the previous RUPTL has further reduced investor confidence, especially considering PLN’s difficulties in implementing large-scale renewable energy procurement,” Yustika said.

Shrinking peak capacity

Tripling the amount of electricity generated by renewable sources appears feasible given that renewable energy projects currently in the planning stages or under construction and slated for delivery over the next decade total nearly 45 GW.

The cost of generating electricity from fossil fuels outstrips solar and wind, according to an IEEFA report published last year. Even accounting for the government support, including below-market price caps on coal sold to domestic power producers, electricity from coal is more than a third more expensive than solar or wind energy.

Even so, whether powered by fossil fuels or renewables, PLN is running out of time to add new generating capacity.

.jpg)

A coal mine in Borneo. Image by Rhett A. Butler/Mongabay.

According to PLN’s latest annual report, power suppliers had, on average, 18% of their installed generating capacity in reserve when demand was at its peak in 2024 — a little more than half of what PLN has said is its minimum.

By comparison, the so-called minimum reserve capacity ballooned to nearly 90% in 2022 when three big coal-fired power stations, including the 1.9 GW Central Java Power Station in Batang, came online.

While PLN argues it is stitching together an electricity generation supply network of fossil fuels and renewables, it is stacking the deck in favor of coal and gas, Hasan of CREA said.

“No coal phase out; no decommissioning and an ambitious gas roll out,” she said.

“Demand for fossil fuels is growing while PLN is kneecapping renewables.”

This article was originally published on Mongabay under the Creative Commons BY NC ND licence. Read the original article.

.jpg)