.jpg)

Coral reef in Vietnam. Image by Björn Frank via Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0).

Vietnam’s first marine protected area, Nha Trang Bay, has lost nearly 200 hectares (494 acres) of coral reef since its creation in 2002, a new study shows. The alarming decline raises fresh questions about how effective conservation efforts have been in protecting one of the country’s most iconic coastal ecosystems.

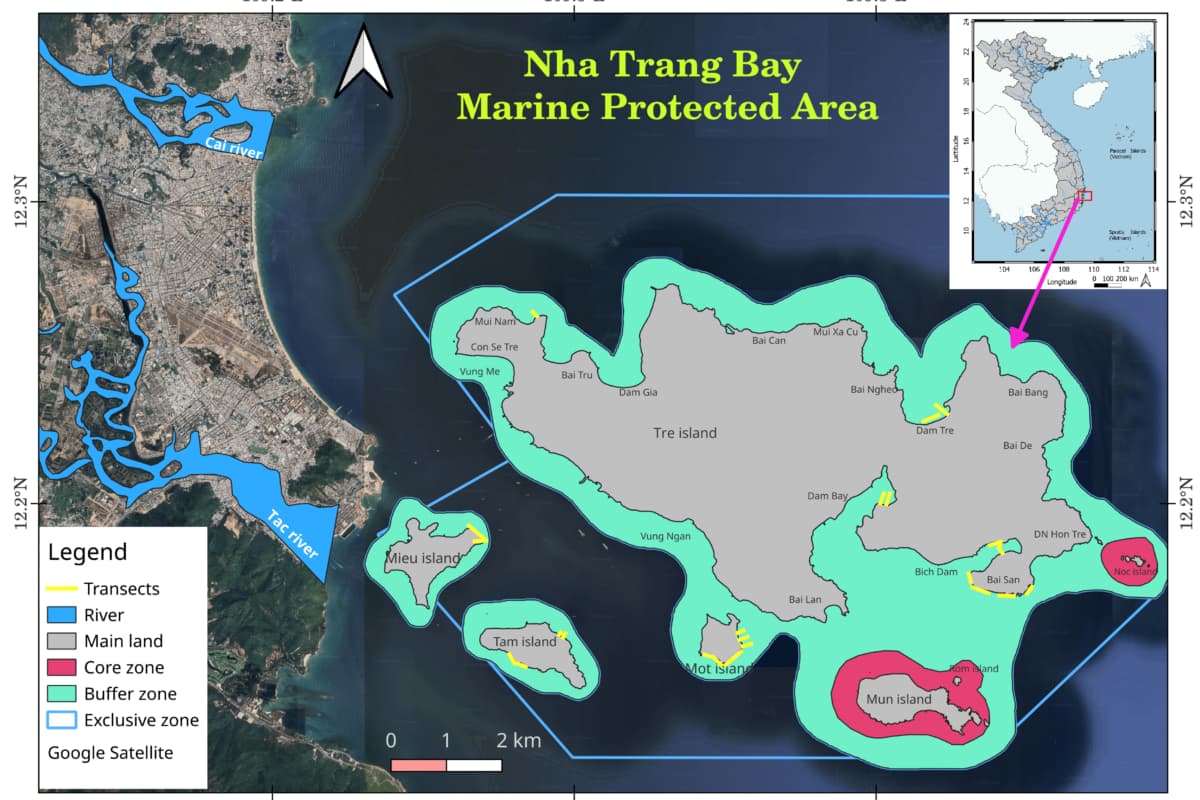

Published in April in the journal Water, the study by the Joint Vietnam-Russia Tropical Science and Technology Research Center used remote sensing and machine learning to track coral changes across Nha Trang Bay’s 160-square-kilometer (62-square-mile) MPA. From 2002-24, about 191 hectares (472 acres) of coral reefs vanished, especially around Tre, Mun, Một, Tằm and Miễu islands.

Despite having protected status since 2002, the bay’s reefs continue to shrink. Key drivers include land use change, warming seas and crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) outbreaks, according to the study. “Among these, land-use change—particularly from long-term landfill activities—emerged as the dominant driver of coral loss,” the authors wrote.

The Nha Trang Bay Marine Protected Area and its functional zones are influenced by the Cai and Tac rivers. Image courtesy of Nguyen Trinh Duc Hieu/ Joint Vietnam-Russia Tropical Science and Technology Research Center.

Hoàng Công Tín is an expert in mapping marine habitats to enable conservation and sustainable use and dean of the Faculty of Environmental Sciences at Vietnam’s Huế University. “Nha Trang Bay’s experience highlights a critical lesson: early designation of MPAs is not sufficient without adaptive, science-based management and active local engagement,” Hoàng, who was not involved in the study, told Mongabay by email.

Coastal development — including the construction of roads, resorts and ports — triggered major land use changes in Nha Trang Bay that led to the loss of 125 hectares (309 acres) of coral reef between 2002 and 2016. The study authors identified backfilling for large tourist complexes, particularly on Tre Island, as a key cause of the coral loss. Pollution from rivers, worsened by urban sprawl and mangrove loss, is also smothering corals with sediment and toxins, they added.

Destructive illegal fishing methods like dynamite and cyanide, along with a rise in unregulated floating fish farms that have worsened nutrient pollution, further damaged Nha Trang Bay’s reefs, according to the study.

.jpg)

Aerial cable cars transport tourists to Tre Island, the largest in Nha Trang Bay. Image by Pixabay via Pexels (Public domain).

.jpg)

Vietnam’s first marine protected area, Nha Trang Bay, has lost nearly 200 hectares (494 acres) of coral reef since 2002, mainly due to coastal development, rising sea temperatures, and crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks worsened by overfishing and pollution, a new study finds. Image by Quang Nguyen Vinh via Pixabay (Public domain).

Additionally, outbreaks of coral-eating crown-of-thorns starfish native to the Indo-Pacific significantly wiped out healthy corals in Nha Trang Bay. The outbreaks, fueled by nutrient pollution and overfishing of the starfish’s natural predators, Triton’s trumpet (Charonia tritonis), led to an average 64% drop in coral cover across 10 monitored sites, the study added.

Rising sea temperatures as a result of global warming are also stressing corals, making them more prone to potentially deadly bleaching, in which the individual animals that form a coral colony expel the symbiotic photosynthetic bacteria that live in their tissues. From 2002-24, the study found, sea surface temperatures in Nha Trang Bay climbed steadily, with several years topping 30° Celsius (86° Fahrenheit) — the heat threshold that triggers coral bleaching. The study authors also noted that 32 typhoons passed through the MPA since its inception and further damaged the reefs.

Hoàng praised the study’s “strong methodological validity” and called its hybrid approach “scientifically robust…scalable and cost-effective for coral reef monitoring in data-limited regions.”

.jpg)

The crown-of-thorns starfish was found in the southwest of Hon Mot. Image courtesy of Nguyen Trinh Duc Hieu/ Joint Vietnam-Russia Tropical Science and Technology Research Center.

He said the most alarming findings were the severe coral losses and starfish outbreaks, noting they reflect “the combined impact of biological disturbances and human pressures like tourism, water pollution, and habitat loss.”

To help Nha Trang Bay’s coral reefs recover and cope with climate change and human pressures, the study authors called for stronger conservation actions, including reducing pollution, redesigning the MPA zones and actively restoring damaged reefs. Just as crucial, they said, is involving local communities and respecting traditional resource rights.

Meanwhile, Hoàng said Nha Trang’s experience reflects risks facing coral reefs across Southeast Asia, particularly in fast-developing or tourist-heavy coastal areas. “These reefs face shared vulnerabilities, including climate stressors, pollution, and unsustainable resource use,” he said. “[F]ailing to act in a timely and coordinated manner may lead to irreversible ecological losses.”

In addition to the study’s recommendations, Hoàng urged Nha Trang and other MPAs to monitor reefs over the long term, set up early-warning systems for threats like crown-of-thorns starfish and make sure coastal development happens only in designated areas.

Hoàng also expressed concern about the rapid decline of seagrass meadows he and other researchers have documented in Nha Trang and other Vietnamese MPAs, like Lý Sơn and Phú Quốc, noting that their degradation mirrors the coral reef losses in both scale and cause. Hoàng’s studies found that Nha Trang Bay lost about 268 hectares (663 acres) of seagrass between 2001 and 2018.

Coral reefs and seagrass beds often coexist in shallow nearshore areas, where they complement each other by stabilizing sediment, providing vital nursery habitats for marine life, and supporting nutrient cycling, carbon sequestration and coastal water quality, Hoang said. Their “fates [are] ecologically intertwined,” he said, so they must be preserved together.

“The degradation of one system often accelerates the decline of the other,” he said. “Preserving one ecosystem cannot succeed without safeguarding the other.”

This article was originally published on Mongabay under the Creative Commons BY NC ND licence. Read the original article.

.jpg)