.jpg)

A freight train in the U.K. run on renewable diesel. Replacing red diesel (fossil diesel specifically earmarked for rail or agricultural vehicles) with RD can cut a train’s emissions by “as much as 90%,” according to the industry. But such claims can be erroneous since some feedstocks have high carbon intensity (such as oil palm) over others (like used cooking oil). Image by Rob Reedman via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Renewable diesel is a biofuel made from vegetable oils and animal fats touted by proponents as an almost miraculous “drop-in” transition fuel able to drastically cut greenhouse gas emissions while easily replacing fossil diesel in all manner of engines.

But this biofuel’s recent sudden surge in production and rapid expansion in applications is alarming environmentalists, who warn unfettered growth could fuel climate change and tropical deforestation.

Renewable diesel, or RD, can be made from a wide range of feedstocks, including waste vegetable oils, animal tallow, corn, canola (rapeseed), soy and oil palm. The feedstock used, where and how it is produced, and whether forests are felled to make way for biofuel crops, all determine RD’s carbon emissions as compared to fossil diesel.

RD is often manufactured in retooled fossil fuel refineries using complex biochemical and thermochemical technologies requiring lots of energy — adding to its carbon footprint. Chevron, BP, Shell and other major fossil fuel companies are now converting excess refinery capacity to make RD and enter the market in a big way.

A big selling point for renewable diesel is that it is almost chemically identical to fossil fuel diesel — meaning it can be substituted in existing diesel engines, making it a so-called drop-in biofuel. (Biodiesel, by comparison, is made using a far simpler process, not requiring manufacture in an oil refinery and not “drop-in”-ready.) An added advantage, RD can be “upgraded” to produce sustainable aviation fuels (or SAF).

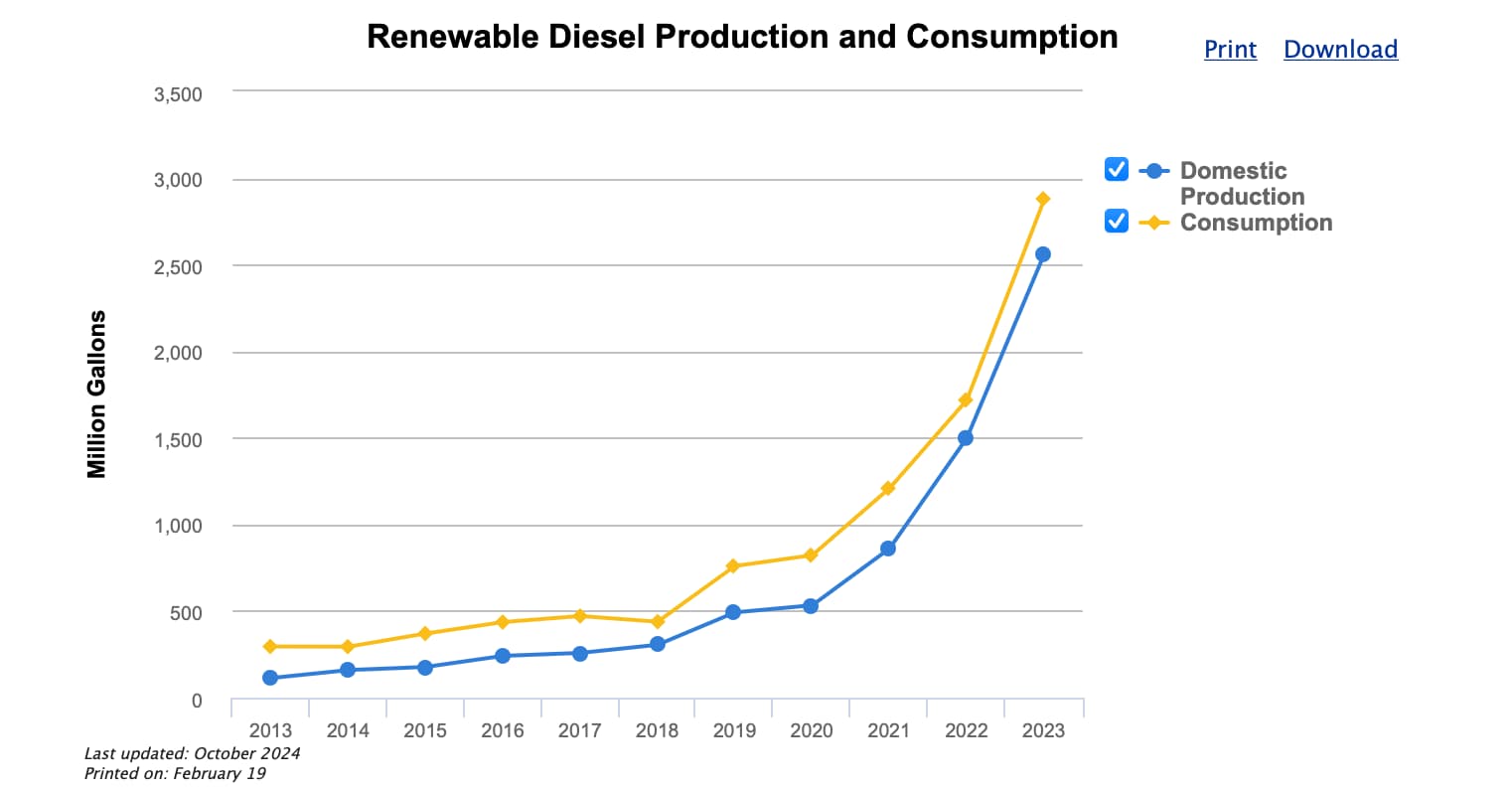

In recent years, renewable diesel production and use has boomed. Global production rose from less than 4 million metric tons in 2014 to 12.45 million metric tons in 2022, jumping to around 23 million metric tons in 2024. This surge could continue in the future, driven by key markets such as the U.S. and EU.

Neste, a Finnish company and the world’s largest renewable diesel producer, estimates that biofuels, including renewable diesel, could replace 1 billion metric tons of fossil fuels in the transport sector alone; the company is currently producing 5.5 million tons of RD annually, known in the industry as HVO (hydrotreated vegetable oil); it aims to sell 6.8 million metric tons in 2026.

Graph showing U.S. renewable diesel production and consumption, last updated October 2024. RD benefits, according to proponents, include its meeting the same fuel quality specifications of fossil diesel, meaning it can be used as a “drop-in” fuel in existing diesel engines and in refueling infrastructure without the need for retrofits or upfits. The problem, say critics, is that there isn’t enough used cooking oil and inedible animal fats to feed the surging RD industry, meaning other sources must be tapped. Image courtesy of the EIA Monthly Energy Review.

Production surge spurred by incentives

Renewable diesel was originally marketed as a cleaner substitute for fossil diesel in hard-to-decarbonize sectors, especially transportation. The U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has never recommended it for use in power plants or other applications.

However, spurred by government green energy incentives, companies are expanding production and targeting new markets, positioning RD as fuel not only for land transport and SAF, but for transoceanic shipping, power plants, as heating oil, and even as backup fuel for energy-hungry data centers. Among prominent green incentives are the EU’s Renewable Energy Directive, the U.S. federal carbon-reduction policies, and especially California’s Low-Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS), and biofuel-friendly mandates in Asia.

In the United States, production (largely sourced from soy) was estimated at just 250 million gallons (946 million liters) in 2013. That’s set to top 5 billion gallons (19 billion liters) this year. Elsewhere, companies in Malaysia and Indonesia have announced plans to develop refineries capable of churning out both renewable diesel and SAF, while Brazil has positioned itself to become a major renewable diesel and SAF producer, adding it to its already vast biofuel industry. Canada, too, is racing to hike production.

Industry critics say that without the lucrative government incentives, RD demand would likely be nonexistent.

.jpg)

Marine shipping contributes about 2% of global carbon emissions. The U.N. International Maritime Organization (IMO) wants to achieve net zero by 2050, particularly by upping biofuel use (including renewable diesel), a move some environmental groups oppose. Image by John Fielding via Flickr (CC BY 2.0).

Rapid expansion concerns environmentalists

International marine shipping offers a good example of what could lie ahead: It already releases 2% of global carbon emissions, so the U.N. International Maritime Organization (IMO) is determined to achieve net zero by 2050, mostly by upping biofuel use. A report by Transport & Environment, a coalition of European NGOs, published in February 2025 found that this push could result in up to 44% of shipping energy demand being met by biofuels (including renewable diesel), by 2035, totaling 105 million metric tons annually.

Earlier this year, this projected surge caused more than 60 environmental and conservation groups to oppose the spread of biofuels in the marine sector in a letter to the IMO.

If the IMO “endorse[s] biofuels as a ‘low-carbon fuel,’ it would lead to more rainforest destruction and land-grabbing while … accelerating climate change,” said Almuth Ernsting, a researcher and campaigner with the NGO Biofuelwatch and one of the signatories of the letter to the IMO. “Communities in the Global South are already bearing the brunt of monoculture [soy and oil palm] plantations — their expansion to feed further growth in biofuels would deepen the crisis.”

The potential expansion of renewable diesel across multiple sectors is “terrifying,” Ernsting concludes, adding that scaling up RD could lead to huge releases of greenhouse gases due to deforestation and land-use change.

“If it wasn’t heavily subsidized economically, the natural demand for this fuel is zero,” says Jeremy Martin, senior scientist and director of fuels policy at the Union of Concerned Scientists. “Vegetable oil is really expensive, and the only reason that it shows up [on the market] is this stack of [green energy] policy supports.”

.jpg)

In the U.S., soybean oil has played a major role in the renewable diesel production boom since 2021. Brazil’s recently passed “Fuel of the Future” legislation includes a “National Program for Green Diesel” (i.e., renewable diesel) that will use soy and other oil crops. Image by U.S. Department of Energy via Wikimedia Commons (Public domain).

A question of carbon intensity: All that grows is not green

As a biofuel, RD has the potential for lower overall greenhouse gas emissions compared to fossil diesel. That’s due, proponents say, to the use of waste feedstocks, and because CO2 released when the fuel is burned is removed from the atmosphere by growing more feedstock crops — the very definition of renewability. But critics say both claims are oversimplifications, with real-world emissions dependent on many factors.

Industry sources also claim that the carbon intensity of renewable diesel — the total CO2 and other greenhouses gases emitted over the life cycle of a product — is far lower than that of fossil diesel. Companies such as industry leader Neste claim greenhouse gas emission reductions of “up to 95%” compared to fossil diesel.

But critics argue there isn’t anywhere near the required waste feedstock globally needed to scale up RD production for multiple uses, which means other sources must be tapped. And those other sources, especially soy and oil palm, could bring with them a high carbon cost from land-use change (particularly tropical deforestation), heavy application of petrochemical-based crop fertilizers, other carbon releases incurred when growing a monoculture, and global transport and RD refinery energy consumption.

Without careful carbon accounting for a scaled-up RD life cycle, this miracle biofuel could even risk emitting more carbon than when fossil diesel is burned, say critics.

.jpg)

A Neste renewable diesel refinery in Rotterdam (the firm also has RD plants in Finland and Singapore). The company, the largest RD producer in the world, confirms that it conducts testing on sourced used cooking oil (UCO) to verify its origins. But critics fear that as demand surges, feedstock fraud will increase in the biofuel sector, with agricultural producers using waste oil labels to conceal virgin palm oil, as its production can contribute to tropical deforestation. Image courtesy of Neste.

To assess these claims and counterclaims, it’s worth looking at how governments evaluate renewable fuels. California, for example, has developed the Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) that requires biofuel manufacturers to quantify the carbon intensity of their products using standard models.

For renewable diesel, the resulting LCFS carbon intensity ranges from 17% to 81% that of fossil diesel. This very wide range is associated primarily with different feedstocks, their associated agricultural practices, and land-use changes. (Scroll down on this page to find the link listing all “current fuel pathways.”)

Soy sourced in the U.S. has among the highest carbon intensities on the California list (while RD made from even higher carbon intensity feedstocks, such as virgin palm oil, do not appear on the California pathways list); domestic used cooking oil or tallow has the lowest carbon intensity, while globally sourced used cooking oil or tallow fall slightly above the mean.

The origin and nature of feedstocks is therefore absolutely key to accurate RD carbon intensity calculations. In this regard, the use of “globally sourced” tallow or used cooking oil, often obtained from third-party sources, is problematic to the California standard because the geographic location and feedstock source are not reported by the companies.

Neste, for example, promotes itself as using only sustainable sources, predominantly used cooking oil, animal fats and vegetable processing waste (including palm oil mill effluent, or POME, and palm fatty acids), that provide a substantially lower carbon intensity than fossil diesel.

But there’s a carbon accounting loophole in the company’s claims: Many of Neste’s products make use of “globally sourced feedstock provided by third parties,” as shown in the firm’s California Low Carbon Fuel Standard Application. What those global sources are, where precisely they’re sourced from, and who those third parties are, is not specified — raising open questions about real-world carbon intensity.

The attribution of “used cooking oil” is another challenge. It is classified as “waste” by the RD industry, so has minimal carbon impact in modeling. That’s despite the fact that the lion’s share of vegetative and animal “wastes” are not truly waste, but are already claimed by established markets other than biofuels. However, if waste is in short supply, then other crops, with higher life-cycle emissions, will need to be grown to meet surging demand.

Usually, the carbon intensity of feedstocks is underestimated, and the greenhouse gas savings overestimated, says Haley Leslie-Bole, senior manager of U.S. lands and climate at the nonprofit World Resources Institute. If renewable diesel were made with “true” wastes, that could mean — in some very few cases — large emissions cuts compared to fossil diesel, she says. “But we’re never going to be seeing that at scale, just because there are not enough wastes to make this [work] as an actual climate solution.”

A palm oil plantation in Sumatra, where industrial agribusiness has contributed heavily to tropical deforestation. Palm oil mill effluent (POME) and palm fatty acids (PFAD) are increasingly used as renewable diesel feedstock, but analysts are concerned about fraud. As with used cooking oil (UCO), alarms are being raised as to whether POME and PFAD are truly waste or intentionally mislabeled virgin palm oil. Image by Rhett A. Butler/Mongabay.

Feedstock availability: A shortage crisis in the making

For Martin, the issue of feedstock availability trumps questions of emissions savings. “I think the focus on life cycle obscures the focus on sustainable availability of feedstocks” required for scale-up, he explains.

The problem, according to analysts: There just isn’t enough used cooking oil or waste animal fats in existence to meet the high projected demand for biofuels like RD, meaning other feedstocks like soy and oil palm are required. Also problematic is that many of these same feedstocks are already under high demand for SAF production.

In 2022, the International Energy Agency warned of a biofuel “feedstock crunch.” In the United States, demand has already “drastically” impacted the global feedstock trade, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Vast amounts of animal fats and vegetable oils are now imported for U.S. RD production and to “backfill” other feedstocks — principally soy oil, which has already become a major renewable diesel feedstock.

Renewable diesel’s problem of scale can only be solved, experts outside the industry say, by siphoning off vegetable oils and other wastes destined for other markets, or by growing vast amounts of alternative feedstocks and with conversion of natural lands to crop lands.

That could ultimately lead to major tropical deforestation and carbon releases, while degrading and destroying natural carbon sinks in places like the Amazon or Indonesia to fill sourcing gaps. This land-use change, even if it is indirect, would significantly negate renewable diesel’s high grades for carbon intensity. Land-use changes and agricultural practices are among the biggest contributors to greenhouse gas emission for biofuels, and the primary reason for varying carbon intensities depending on feedstock.

“If people were [already] making soaps and detergents out of tallow or used cooking oil, and now that’s all sent to California to make renewable diesel fuel, what are [soap makers] going to use?” Martin asks. “If that’s all redirected to renewable diesel fuel production, then those products will [have to] be made from palm oil. Will we have really accomplished anything?”

Rising renewable diesel demand, shortages of used cooking oil, and high prices, have already sparked accusations of fraud due to false labeling of European RD feedstock imports from China, Malaysia and Indonesia. It’s believed large amounts have been sourced not from waste as claimed, but made from virgin palm oil. Similar accusations have arisen in the U.S., amid a rapid increase in cooking oil imports from China in 2024.

.jpg)

Chevron has converted a fossil diesel unit at its El Segundo refinery in Los Angeles to make renewable diesel. The refinery is capable of producing up to 10,000 barrels a day. California’s diesel consumption is now made up of around 80% biofuels, claimed as a climate win by some and incredibly troubling by others. Image by Pedro Szekely via Wikimedia Commons (Public domain).

Whether renewable diesel producers are truly using sustainable waste feedstocks as claimed, and not virgin palm oil, is questionable, says Cian Delaney, campaign coordinator at Transport & Environment. Other feedstocks involved in this controversy include palm oil mill effluent (or POME) and palm fatty acids, both used to make renewable diesel.

A recent report from Transport & Environment found that, in 2023, the EU and U.K. used around 2 million metric tons of POME (mostly for renewable diesel), set against global POME production of 1 million metric tons for that year. That raises concerns that POME is virgin palm oil “in disguise,” the organization says.

Four European nations — Ireland, Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands — recently acknowledged that the suspected use of virgin palm oil masquerading as waste is “a cause for concern” and called for an investigation. Earlier this year, the Indonesian government announced regulations on exports due to discrepancies in the volumes of domestic palm waste production and those shipped to other markets. The U.K. government is also investigating fraud in renewable diesel sold in the country, due to links to virgin palm oil use, according to the BBC.

Renewable diesel, called HVO (hydrotreated vegetable oil) by the industry, has been touted as a climate solution for the hard to decarbonize transportation sector. But critics say that, when scaling up production, RD’s sustainability claims become inflated and possibly dubious. Image by Steve Knight via Flickr (CC BY 2.0).

The rush to burn renewable diesel

Multiple industries hooked on fossil diesel are now looking to its “renewable” form as a climate solution, possibly turning a blind eye toward the potential for tropical deforestation and high life-cycle emissions risks.

Tests are underway to directly replace heating oil in the U.K. with renewable diesel, to generate electricity using RD at a U.S. federal Tennessee Valley Authority power plant, and at a power plant in Germany. Elsewhere, Amazon Web Services, Meta and other companies are experimenting with RD to supplant fossil diesel in backup generators at data centers.

Neste, with RD refineries in Finland, the Netherlands and Singapore, says it is exploring renewable diesel’s potential in multiple sectors, including mining, construction, rail transportation, and the maritime sector.

“The product, by definition, is usable wherever diesel is used. So, this means [renewable diesel has a place] in every kind of hard to abate heavy duty [fossil diesel] application,” says Joerg Huebeler, head of market development at Neste. The firm expects waste used to produce fuel to grow by around 40 million metric tons per year by 2030. “We see there’s a huge potential in this waste and residue-based feedstock pool,” he explains.

But experts note that this “burn renewable diesel everywhere” strategy raises hard questions about the availability and sustainability of already strained waste feedstocks. Ramping up RD use for marine transport, heating, power plants and data centers means yet more competition for an already limited resource.

“I don’t see how all of these different industries and countries can all think they can run on used cooking oil,” Delaney says.

Trouble in the tropics

In Brazil, planned expansion into renewable diesel is causing environmental concern, especially related to deforestation in the Amazon Rainforest and Cerrado savanna. Brazil’s recently passed “Fuel of the Future” legislation includes a “National Program for Green Diesel” (i.e., renewable diesel), as part of the country’s already mammoth biofuels industry.

As of 2024, there was no commercial RD production in Brazil, but announcements by companies such as Petrobras and Riograndese indicate RD and SAF refineries are coming, with plans to use soy and beef tallow as feedstock. Acelen Renewables and Embrapa Agroenergia also plan to “create genetically identical copies of superior macaúba [trees]” to be grown on new plantations and refined into RD and SAF. Macaúba is a tropical palm with promise of high seed oil production; its carbon intensity is as yet unknown.

Research published last year found that Brazil’s biofuel industry, together with the agricultural sector, is already one of the biggest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions in the country. Biofuels (including biodiesel made from soy, oil palm and tallow) are closely tied to deforestation and to intentionally set wildfires to clear new pasture and croplands. In an extensive investigation, Mongabay found strong evidence in Brazil of fraudulent land titles, deforestation and abuses of traditional communities in connection with oil palm production for biofuels.

Sustainability claims are being hugely undermined by deforestation, says Eder Johnson de Area Leão Pereira, professor of economics at the Federal Institute of Maranhão. “When we talk about biofuels, people think that those are clean, and that those alternative fuels will not impact the climate or the environment,” Pereira says. “We found that is not the case in Brazil due to connections within the agricultural industry.”

.jpg)

A cattle ranch in Acre, Brazil, showing deforestation. Beef tallow, essentially cow fat, is in demand as renewable diesel feedstock. In 2022, Brazil’s JBS supplied 450,000 metric tons to RD makers in the U.S., Australia and Canada. A lack of corporate or government traceability obscures whether this tallow is tied to deforestation, says André Campos, research manager at Repórter Brasil. Deforestation has been a chronic issue with JBS. Image by Kate Evans/CIFOR via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Brazil is already exporting problematic renewable diesel feedstocks. In 2022, journalists at Repórter Brasil documented the unsustainable trade in beef tallow for biofuels imported into the European Union. (Brazil’s cattle industry is the nation’s leading cause of deforestation.)

In recent years, Brazil also began exporting vast quantities of tallow to the U.S. for renewable diesel production; in 2021, it exported around 22,000 metric tons; by 2024, this jumped to more than 280,000 metric tons.

André Campos, research manager at Repórter Brasil and a lead author on its story, says claims that beef tallow sourced from Brazil is environmentally friendly and a “circular” solution are “simply not true.” His research highlights connections to cattle giant JBS, which supplies tallow for SAF production. JBS is notorious for turning a blind eye to illegal deforestation.

“There is no traceability system that guarantees this product isn’t coming from areas linked directly or indirectly to recent deforestation,” Campos says. “I think the concern is more relevant than ever, considering that the use of this product is spreading to multiple markets right now.”

Arguing successfully that RD produced using Brazilian beef tallow is sustainable is very difficult, adds Lucas Ferrante, a researcher at the University of São Paulo. He fears rising demand for energy crops will lead to deforestation in the Amazon, Pantanal and Cerrado biomes.

“Furthermore, recent cycles of deforestation — driven both by biofuel crop plantations and cattle ranching — have led to severe violations of Indigenous rights and increased invasions of their territories,” he wrote in an email.

.jpg)

Oil industry giants like Chevron, BP, Shell and TotalEnergies are planning to refit existing oil refineries or build new biofuel plants to produce renewable diesel. A report by the NGO Biofuelwatch describes the spike in renewable diesel (utilizing tallow) as a “fat grab.” Image by Glenn Euloth via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Fossil fuel firms jump into the ‘green diesel’ game

The oil and gas sector, lured by alternative-energy financial incentives, are now jumping into the renewable diesel market.

Based on an analysis published last year, Chevron, BP, Shell, TotalEnergies and others are planning to refit oil refineries or build 43 biofuel projects capable of producing 260,000 barrels a day by 2030, with the majority making RD and SAF.

That’s partly to avoid being left with stranded fossil fuel assets if climate laws become more stringent, says Leslie-Bole from the World Resources Institute. But in places like California, state incentives are driving the switch. Martin, from the Union of Concerned Scientists, notes that the costs of remediating refinery pollution, and the allure of incentives, are motivators, but so too is telling a “green story.”

“I think oil companies are under pressure to come up with a climate plan, so they have an interest in promoting this as an alternative to phasing out combustion fuel,” he says.

The U.S.-based Environmental Integrity Project warns in a report that U.S. biofuel refineries can cause more pollution than fossil fuel refineries when it comes to carcinogenic air pollutants, including acetaldehyde, acrolein, formaldehyde and hexane.

“I think there’s a lot more research that needs to be done on exactly what the human health impacts are [of renewable diesel], but there’s enough research already for us to know that there are health impacts,” says Leslie-Bole. “We shouldn’t just say this is better for air quality because it’s more complicated than that.”

Industry claims that RD reduces harmful air pollution by lowering toxic pollutant emissions such as nitrogen oxides and particulate matter from vehicle tailpipes, compared to fossil diesel. But experts say looking beyond tailpipe emissions complicates these cleaner claims.

Because the refining of renewable diesel requires vast quantities of hydrogen, an increase in RD production will also require more of this gas. But most of the world’s hydrogen supply is currently made using fossil energy sources, meaning more carbon emissions and air pollution. Couple this with increased flaring at refineries and pollution from the global distribution network as feedstocks are moved from fields to refineries, and the image of RD as a climate and air pollution solution grows more problematic, say experts.

.jpg)

Renewable diesel is available as an fossil diesel alternative at filling stations in many nations, including Spain, Germany, and the Republic of Ireland. Neste, the world’s leading RD producer, claims, “Carbon emissions from the use of renewable diesel amount to zero, as the amount of carbon dioxide released upon combustion equals the amount that renewable raw material has absorbed earlier.” But this oversimplified view is misleading, as it fails to add up carbon emissions across the RD life cycle, or account for high carbon intensity feedstocks. Image by IADE-Michoko via Pixabay (Public domain).

Can ‘green diesel’ truly be green?

With the U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Agreement for a second time, and other nations falling far short of their carbon cut pledges, the window to avoid catastrophic global temperature increases is closing. So the need to implement clean energy solutions for highly emitting sectors such as transportation is more urgent than ever.

However, the experts interviewed for this story said that, due to constraints on truly sustainable feedstocks, renewable diesel is unlikely to bring anything near the emission reductions needed, and RD could even exacerbate the triple crisis of climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution.

“We’re already coming up against the sustainable limits of what we see to be a low-risk application of these feedstocks,” says Jane O’Malley, a senior fuels researcher at the International Council on Clean Transportation, an NGO. Delaney, who is skeptical that RD can actually achieve its emissions-cutting role, emphasizes that other solutions such as electrification of transportation should be prioritized.

Those interviewed also agree that it is government policy, especially biofuel mandates, feedstock caps, and the offering or withdrawal of incentives, that will restrain or fuel renewable diesel growth.

According to Scott Irwin, an agricultural economist at the University of Illinois, the U.S. renewable diesel boom may already be waning, with production topping out at around 5 billion gallons for the foreseeable future. The Trump administration, with its emphasis on fossil fuel drilling, may stymie growth for now.

Or, “The industry could be rebooted into a more rapid expansion phase if the Trump administration decides to go for an aggressive implementation of the Renewable Fuel Standards,” says Irwin. “I think that’s unlikely, but it’s possible.”

Martin is calling for caps on feedstocks in markets such as California. “I think the renewable diesel market is growing at an unsustainable and damaging pace, and we need to add safeguards to make sure the growth of that industry is consistent with the availability and sustainability of the underlying feedstocks and resources,” he says.

The risk of uncontrolled expansion, according to campaigners like Ernsting from Biofuelwatch, is that creative carbon accounting applied to biofuels will simply aid humanity in blowing past its global emission reduction goals. Of renewable diesel, she says: “It’ll just make climate change even worse, even faster.”

This article was originally published on Mongabay under the Creative Commons BY NC ND licence. Read the original article.

.jpg)